The sweetness of peaches

What’s left when the bees are gone ...

She found the heart-shaped locket lying on the corner of 81st and 2nd Avenue in Manhattan. Or what was left of that place where she’d once walked with Harold on their way to the diner for her usual mundane order of scrambled eggs on white toast with black coffee. She never imagined that things, the world, or whatever you wanted to call it now that it was gone and in tatters, would end this way.

When she was a little girl, she was terrified of bees. She imagined in the future everyone dressed in spacesuits to protect themselves from the swarms of Africanized honeybees who’d finally made it North. She’d been stung by Yellowjackets a few times when she was a girl growing up in Hartford, while running through the sprinklers barefoot on the grassy summer lawn. It's what taught her about power. It had nothing to do with size or muscle or might. Ants could move mountains and bees could kill.

She could still remember the day when she reached into the lavender in her mother’s garden to pick one of the purple, fragrant flowers that calmed her worries for the future, at least for a minute, and out came a bumble bee resting on the back of her hand.

“If there’s a God,” she spoke to the bee. “You won’t sting me.”

The bee flew away, innocently, without incident. That’s when she started secretly believing. Her atheist parents who avoided churches like the plague would never have to know.

Her parents were gone, like most of humanity who tore each other apart and otherwise gave up. The bees were rumored to still live in faraway places like Romania, but the collapse of society meant that there were was no way to get there, unless on a makeshift boat, and Layla Rose was no seafaring sailor.

As far as her Irish green eyes could see, all that was left was God and the empty world he’d created with his legions of overly optimistic humans, who thought everything would work out with or without the bees.

She wondered if the smiling young soldier in the battered golden locket she’d placed in her pocket was ever stung by a bee and if he could have ever imagined living off peaches and instant coffee. Perhaps. She was old enough to know that World War II was another kind of brutal.

She’d asked Joe if they could take a ride through Manhattan one last time. Harold was long gone. Her steady husband of over twenty years, her college boyfriend who she met in French Lit at Columbia, had hurled himself off of the George Washington Bridge. He was Jewish and couldn’t take the thought of starvation. It was an ancestral fear, and a chaotic, uncertain world without lox, capers, and smears of luscious cream cheese wasn’t for him.

After Harold jumped and no one was around to save him, she caught one of the last Amtraks out of Penn Station, filled with people heading for Florida, where they thought they could make it. She jumped off in Savannah and started walking to find a river to bathe. Harold always said women were the stronger sex.

In rural Georgia, she’d met Joe. Before him, she spent her days wandering alone in old empty houses, the ones with wide awnings and porches that made her yearn for sweet tea. She’d used her one good flashlight in dark basements and dusty pantries to find the odd jar of canned peaches inside a glistening Mason jar.

God bless the woman who preserves, she said to herself, as she looked around for more instant coffee to add to her stash.

Joe was younger than her, although she didn’t know exactly by how much. Questions with irrelevant answers had, along with everything else, become a thing of the past. He had grown up in rural Georgia hunting in the woods and fishing in the rivers, so he knew how to kill things with ease and precision.

Layla wasn’t sure how she got so lucky.

There were other hunters like him everywhere, hiding in some woodsy warren, becoming more savage by the day. Without fuel or electricity, it was the Middle Ages again when no one knew anymore what was over the horizon, and without any television and radio narratives clogging the airwaves, there wasn’t much of a need to know.

Joe had almost shot her dead thinking she was a deer when they first crossed paths on the empty dirt road somewhere outside of Statesboro, not long after she’d walked across an old empty college campus that had once spun out educators. She knew that particular detail because she’d applied there once for her Master’s degree but never followed through. Teaching was a noble profession but instead she’d sold out and worked her whole life in advertising on Madison Avenue.

Georgia, as a place, always called to her. Whenever she had the occasion to say its name, a little more electricity ran over her nerve endings. She often suggested taking trips there to Harold, but he’d always shoot back, “What’s wrong with the Poconos?” He hated flying.

Little did she know that she and Georgia, or was it Georgia and her, (grammar was escaping her too), would finally meet up during the post-apiary Apocalypse.

After Joe lowered his rifle and she looked past his tangled long hair and unruly beard and saw the overwhelming kindness pouring from his blue eyes, she broke their wary silence first.

“Do you like peaches?” she’d said, and he nodded. He’d later whisper into her ear that he wanted nothing more than to taste their sweetness.

While she cast her flashlight around looking for more peaches to carry around in the heavy pack Harold said she’d never need because he’d never take her camping in the wild, Joe looked for the old tackle boxes and the cartons of bullets leftover from all the right-wing conservative Yankee-hating gun enthusiast hoarders who’d stocked up when their favorite Ken and Barbie-doll news networks had them convinced that Dems were taking their freedoms and guns away.

They should have paid more attention to the other news reports, she thought. The ones about the vanishing bees.

As she wandered through yet another empty house filled with giant safes that weighed more than baby elephants, she thought of how all the guns they amassed—when Obama was president, when Hillary was running, and when Biden took office—would never see the light of day again, unless a meteor came along and blasted them free. All the old bullets Joe found in closets or lying around on workbenches, meant to protect life, limb, and liberty, were now saving her left-wing liberal ass. That was what she loved most about the end of the world: the beautiful ironies.

Joe was one of the “Patriots,” whose losing ancestors had fought for the British and for General Lee. He’d once hoarded guns while he worked as an auto mechanic somewhere outside of Atlanta in his earlier years. As was his ancestral duty, he expressed his qualms about traveling with a Yankee after she told him she’d grown up in Hartford, Connecticut, daughter of the winning ancestors of the Revolutionary and Civil Wars.

“You’re lucky I love peaches so much,” he’d said with a wink and a smile. It was nothing short of miraculous to Layla that the world could end but two surviving humans from opposing sides of the old political fences could find it in themselves to flirt and feel butterflies again.

While they foraged for peaches and bullets, their bond was immediate and unbreakable. The total absence of humanity had made that possible. They hugged hard and close the night after they met, which felt as necessary as any scrap of food. If they felt a petty argument coming on over something trivial, like which way to walk next, they’d take deep breaths and let the prickly feelings pass. The value of each other’s company was more than either had counted on.

A few days after they met on the road, they kissed messy and fast in some old mansion, in someone’s old dusty four-poster bed, and got swept up with all of the passions they had left to give. They had to be careful though. Not for fear of pregnancy, Layla was too old for that, but for fear of expending too much energy without having enough food to recover their strength to keep on going.

Most of the time, Joe’s searches for guns and bullets would end in some Southern cussing, which always made Layla laugh, another priceless commodity. There wasn’t a day that Joe didn’t express his wish to have the kind of magical mental powers that gave up the many safes’ secret numbers. Every time he went missing for too long, she could usually find him in some closet twirling a lock with his left hand, ear pressed against the metal, listening intently to the sound of its clicks.

“What the hell you wanna go to New York for?” He’d asked when she first made the suggestion. It’s not like they had a good reason to travel a thousand miles. “Manhattan has to be dangerous.”

“Betcha there’s a lot of interesting loot to be had in all those old corner stores,” she said to pique his interest, and, predictably, he came around to the idea. Living off of venison jerky, peaches, and instant coffee was hard going, even if the long intimate nights were making up for some of the depravity.

“We can go fishing in Pennsylvania and see what else we find on our way.” With Joe’s mechanical skillset, she knew they could make it. There was some fuel to be found in the old abandoned gas stations and there were old cars and trucks everywhere, the vintage kind that could come alive with the crossing of some wires.

“But we have everything we need around here.”

“If we don’t go now, spring will turn to summer and everything will expire and rot. We’ll find a trailer and fill it up with whatever we can find. What have we got to lose?”

As close as they’d become, she didn’t confess that she secretly wanted to say goodbye to New York, one last time, before winter came, before she couldn’t go on anymore, wandering through the end of time.

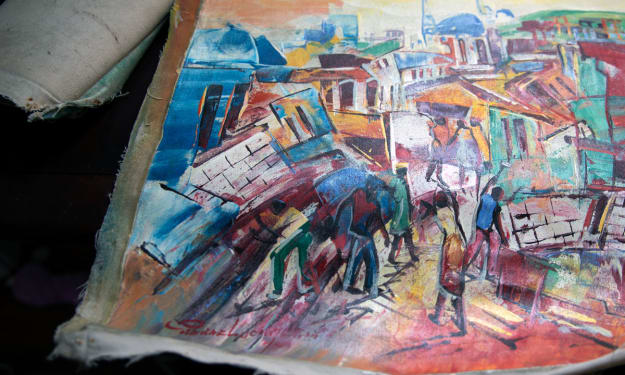

She’d once loved Manhattan for the bagels, the bookstores, and the people watching in Central Park. Museums, once in a while, but not too much, since artwork hung on a plain-white sterile wall always felt a little depressing on behalf of the painters who’d sat in far more interesting environments to create them. Monet and Renoir had sat fat and happy on the banks of meandering rivers outside of Paris on sunny breezy days eating cheese, baguettes, smoking and drinking red wine while they chose a color from their palettes. Picasso had made love to beautiful women in his studio in between paint strokes before a feast and a smoke a Gauloise on the terrace.

Layla noticed how she wasn’t thinking so much about the art museums anymore but about the good sex and the food. The end of the world boiled things down like that. Harold hadn’t been much of a lover; they’d only had perfunctory sex once in a blue moon. He liked to talk, mostly critically about some book or movie he thought needed deconstructing.

If she could do life over again she would have ravished more lovers and cared less about the safe institution of marriage. The feel of grabbing Joe’s smooth bronzed skin under her nails was an indescribable pleasure she’d never allowed herself in the old world. She lay awake at night clinging to his chest just to listen to his heart beat. After all the living, working, and worrying about the end of the world coming, it was the only sound that made any sense anymore. It was the sound of God.

It was the distant hum of a bee.

About the Creator

Heidi Reed

Heidi Reed started writing short stories at the age of fourteen and never stopped, always dreaming of becoming a professional writer one day. She recently self-published her memoir on Amazon called "Sight Unseen: A true story."

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.